Le pari que la Chine va s'effondrer

Chinese Investment: The Slow Grind Ahead

By Adam Wolfe

RGE Share | Jun 23, 2010 | Last Updated

Chinese investment is likely to peak near 50% of GDP in 2010 or 2011. In the coming years, cyclical factors, like the removal of the fiscal and monetary stimulus measures from late 2008, will slow the rate of investment growth. Structural forces, like the coming peak of the country's labor force, will permanently increase the cost of capital in China and limit the government's ability to ramp up investment to the pace of 2009. While this transition will herald the beginning of a long awaited turn in China's economic structure toward domestic consumption, it also will usher in an era of lower growth rates. A study of other Asian economies that have made this transition suggests that the risk of a financial crisis will be elevated in the next few years, though the process need not be catastrophic. Judging from the June 19 return to a managed float for the renminbi and the discussion surrounding the drafting of the next Five-Year Plan for the economy, it appears that policy makers are aware of these risks. Although financial repression will help to ensure that China's banking sector survives the transition toward consumption-led growth, in the medium term the financial sector will need to be reformed or China's growth will slow even further. Regardless, lower growth rates going forward will be unavoidable for China. Its current account surplus may increase slightly as the slowdown in investment growth outpaces the decline in China's savings rate, which would challenge global rebalancing.

Chinese investment is likely to peak near 50% of GDP in 2010 or 2011. In the coming years, cyclical factors, like the removal of the fiscal and monetary stimulus measures from late 2008, will slow the rate of investment growth. Structural forces, like the coming peak of the country's labor force, will permanently increase the cost of capital in China and limit the government's ability to ramp up investment to the pace of 2009. While this transition will herald the beginning of a long awaited turn in China's economic structure toward domestic consumption, it also will usher in an era of lower growth rates. A study of other Asian economies that have made this transition suggests that the risk of a financial crisis will be elevated in the next few years, though the process need not be catastrophic. Judging from the June 19 return to a managed float for the renminbi and the discussion surrounding the drafting of the next Five-Year Plan for the economy, it appears that policy makers are aware of these risks. Although financial repression will help to ensure that China's banking sector survives the transition toward consumption-led growth, in the medium term the financial sector will need to be reformed or China's growth will slow even further. Regardless, lower growth rates going forward will be unavoidable for China. Its current account surplus may increase slightly as the slowdown in investment growth outpaces the decline in China's savings rate, which would challenge global rebalancing.

I. The Argument: Investment Flows Will Slow, Capital Accumulation Will Continue

This is an argument that the relative flow of Chinese investment is peaking. No economy is productive enough to consistently take 50% of its GDP each year and invest it in fixed assets without a drop in returns. This year or next, gross fixed capital formation's share of GDP is likely to peak near 50% in China for several reasons described hereafter. This does not mean that investment will suddenly come to a stop, though investment growth is likely to slow going forward as private consumption growth begins to tick upward.

This is not an argument that China's infrastructure is overdeveloped or that China's capital stock is more than sufficient for its economy. Clearly China's capital stock remains relatively low, and there are plenty of opportunities for productive investments that will continue to pay relatively high returns compared to investments in more advanced economies. A rough estimate would put China's per-capita capital stock at less than one-fourth that of the U.S. on a purchasing power parity basis. Certainly China has several years of capital construction ahead of it, and much of this investment will be directed to productive ends.

A study of the Asian economies that have been through this cycle suggests that when the share of investment in GDP peaks, growth slows and the risk of financial crisis increases sharply. Nine Asian countries have seen investment peak as a share of their GDP: the Philippines (1983), Singapore (1984), Hong Kong (1997), Japan (1990), South Korea (1991), Taiwan (1993), Thailand (1995), Indonesia (1996) and Malaysia (1995). At least five of these countries experienced financial crises that corresponded with investment peaking as a share of GDP. In the five years following the investment peak, growth in these countries slowed an average of 62% compared to the previous five years. Each country's probability of experiencing a year of negative growth increased to 22% in the year following the peak, compared to 7% for any other year.

Given these precedents, China is clearly entering dangerous territory, but there are reasons to believe that it will escape the worst of it. China appears able to control the speed at which investment slows and thereby avoid a financial crisis, like South Korea and Taiwan before it. This year's drafting of the next Five-Year Plan, aimed at guiding the economy toward domestic consumption, will be key for resilience during this transition. The central bank's return to a basket-band crawl for the RMB on June 19, 2010, should help boost consumption slightly during the transition and decrease the risk of a harder landing for the overall economy.

II. The Context: The Experience of Other Asian Economies

Investment has peaked as a percentage of GDP in nine Asian economies for various reasons, but a country's income level, an imperfect estimate of its capital stock, has not been a significant factor. In this sample, there has been a weak negative relationship between GDP per capita (on a purchasing power parity basis) and the level at which gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) peaked as a share of GDP—lower income countries appear slightly more able to direct a larger portion of their GDP toward investment before reaching the peak. Though GFCF's share of GDP has peaked at a wide variety of levels in countries with a wide variety of income levels, in these countries GFCF peaked at an average of 36% of GDP when GDP per-capita was US$13,300 in 2005 dollars on a purchasing power parity basis. The predictive power of the relationship is weak, but there is no reason to believe that China's investment could not peak at its current income level (three countries reached the peak at a lower income level than China's in 2009). Meanwhile, the share of China's GDP directed toward investment is hovering on the outer frontier of this sample set (only Singapore reached a GFCF/GDP ratio of more than 45%).

Figure 1: Weak Relationship Between Incomes and Investment Peak

Source: National Statistics, Gapminder, RGE

When investment has peaked in other Asia economies, more often than not (five times out of nine) this has occurred alongside a financial crisis. Though this appears to have complicated the transition to consumer-led growth and resulted in lower overall output growth, the cause and effect here is a bit mixed. In some cases, as in Hong Kong, external events sparked a financial crisis that required credit rationing, which caused the flow of investment to slow. In other cases, like those of Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, investment peaked as a share of GDP just before the onset of a financial crisis. Certainly there were unique factors in these countries' financial systems that are not currently present in China (namely, Chinese banks do not appear to have taken on much currency risk by borrowing abroad as their lending is mostly funded by deposits). Still, historical evidence suggests that when the flow of funds toward investment begins to recede, bad loans will start to appear.

After investment peaked as a share of GDP, the countries' growth rates invariably slowed. On average the nine Asian countries in this study saw their average annual growth rates decelerate by 4.3 percentage points, from 7.4% in the five years preceding the peak to 3.1% in the following five years. Even when countries that experienced a financial crisis in the years following the investment peak are excluded, growth slowed an average of 2.4 percentage points, from 8.7% to 6.3%.

III. The Driving Forces: Why Chinese Investment Will Slow Further

There are multiple factors causing a slowdown in Chinese investment flows, including structural reasons, such as the rising cost of capital, and cyclical reasons, such as the withdrawal of infrastructure-heavy stimulus measures. Although cyclical factors will likely provide the initial push, structural factors will ensure that investment does not regain its 50% share of GDP in the coming decade. A cyclical slowdown in investment growth is already underway, as RGE forecast in the 2010 Outlook, with only real estate investment propping up the overall fixed-asset investment (FAI) growth rate near its recent trend. Next year, FAI growth will slip below trend. Though structural factors are only now taking root, wage growth soon will outpace productivity growth and capital accumulation will slow as the labor force peaks in 2014. These structural changes will result in a slightly higher cost of capital and lower returns on additional investment, preventing another surge in GFCF like we saw in 2009.

The Cyclical Factors

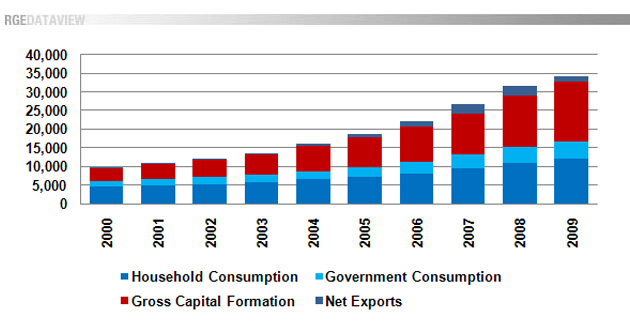

Investment will peak as a percentage of GDP for the same reason that investment climbed to its dramatic high last year: fiscal stimulus and ultra-loose monetary conditions. Thanks to a RMB4 trillion (US$586 billion) fiscal stimulus announced in November 2008 and RMB10.8 trillion (US$1.6 trillion) in new bank lending from November 2008 through December 2009, Chinese GFCF's share of GDP increased from 41.7% in 2007 to 47.5% in 2009. Going forward, these supportive measures will have to be removed or asset price inflation will get out of hand. GFCF growth already has begun to slow in 2010, but it continues to outpace consumption. In 2011 or 2012, consumption will begin to outpace investment, and fixed capital formation will begin to decline as a share of GDP.

Figure 2: Investment's Growing Share of the Pie (billions RMB)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, RGE

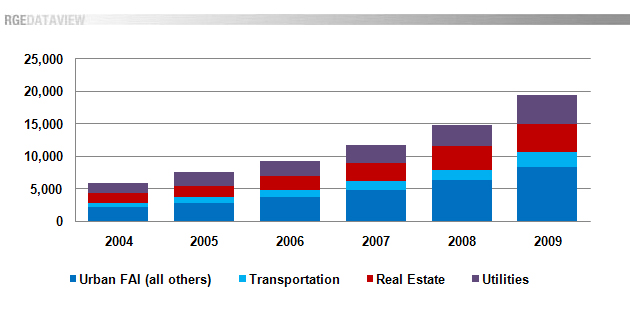

Although some of the stimulus was directed to social services and other non-investment activities, the bulk of the funds went into an acceleration of China's infrastructure development. Before Lehman Brothers collapsed, China's rail network expansion was expected to be completed by 2020. The government brought the deadline forward to 2012 to stimulate the economy, resulting in a 70% increase in railway investments in 2009. Another RMB700 billion (US$102 billion) is budgeted for high-speed railways in 2010. This investment may well prove profitable, as it will free up some rail capacity for commodity shipments instead of passenger traffic and allow manufacturers to relocate further inland to reduce their labor costs. Still, the pace of investment will prove impossible to sustain beyond 2011, when many of the projects should be completed.

Equally impossible to sustain are investment increases in 2009 that will contribute to the urbanization of China's Tier 2 and 3 cities. Investment in highways increased 41%, investment in water and environmental management rose 45% and wind energy investments doubled. For the past five years, installed wind-power capacity in China has doubled every year, and the government's 2020 goal already has been achieved. Yet most of this capacity was never connected to the grid, and only 0.75% of China's electricity generation came from wind power in 2009. A new quota system will force power companies to buy some wind energy, and an upgrade to the country's grid is in order, but funds cannot flow into unused and unprofitable capacity upgrades at the same pace. There will continue to be areas of investment opportunity in China's infrastructure, but most of the low-hanging fruit already has been picked, and the marginal returns will decline going forward.

Figure 3: Fastest Growing Investment Sectors to Slow (billions RMB)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, RGE

In H1 2010, a rapid increase in real estate investment mostly offset the decline in infrastructure investment growth, but government policies aiming to cool the property markets will weigh on real estate investment going into 2011. Through May, real estate investment increased 38.2% y/y despite the announcement in mid-April of harsh regulatory measures to discourage speculative demand. Real estate developers were already facing tighter domestic borrowing conditions, but they were able to raise funds offshore to maintain their elevated investment levels. Going forward, increased RMB volatility and falling Chinese property prices will further increase borrowing costs for China's real estate developers. This will temper real estate investment growth, though plans to expand the supply of affordable housing should prevent a serious deceleration like that in 2008-09.

Figure 4: Real Estate Investment Is Preventing a Broader Slowdown (YTD, % y/y)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

This is not to say that China's infrastructure is overdeveloped (though in some areas it is) or that much of this investment will go to waste (though some local leaders chose vanity over productivity in selecting investments). Projects like the recently announced plan to build urban rail networks in 25 cities by 2015 and plans to expand affordable housing and upgrade the electrical grid will help keep investment elevated for the next five years. Still, the pace of investment is likely to ease as marginal returns decline and credit and fiscal spending growth slow.

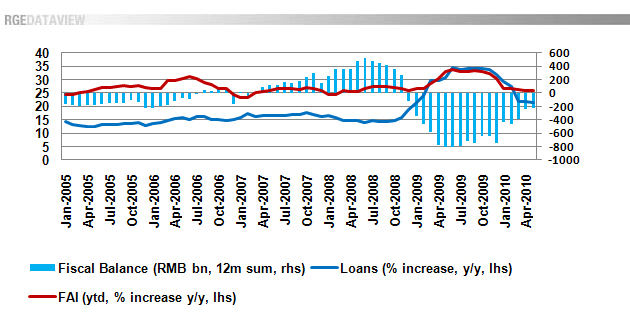

Chinese investment reached its peak on the back of a massive monetary and fiscal expansion that is unlikely to be repeated anytime soon. China has the fiscal space for another modest stimulus should a slowdown of global growth weigh on the domestic economy in late 2010 or early 2011, but that space is much more constrained than it was in 2008. As RGE has noted in the past, the squeeze on local governments is severe. In 2009 local governments were able to borrow at least RMB4.3 trillion (US$633 billion) from banks through urban development and investment companies (UDICs), which act like special investment vehicles (SIVs) for the local leaders. UDIC loans outstanding increased by more than 70% in 2009 to RMB7.4 trillion, according to government estimates. On top of this, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) guaranteed RMB200 billion worth of bonds for local governments, while UDICs issued more than RMB250 worth of corporate bonds. Government land sales generated an additional RMB1.6 trillion for local coffers in 2009, up 63% y/y, which will help keep investment elevated for the rest of 2010. However, these financing channels are all strained: Property regulations are weighing on land sales, the MoF opted not to increase the amount of local bonds it will sell in 2010 and UDIC borrowing is the target of a regulatory investigation. Although local ingenuity will likely tap into another source of funding for investments to replace UDIC borrowing (most likely government-linked private equity), the hangover from 2009's bender will limit the government's ability to grow investment at such a rapid rate for years to come.

China's consolidated government debt is close to 70% of GDP when local government debt and contingent liabilities are included, much higher than the 20% of GDP accounted for by the central government. That doesn't signal a fiscal sustainability problem—even if growth slows to 8% for the next decade China can easily outgrow this debt level—but the government will not be able to ramp up its contingent liabilities like it did in 2009 to foster another investment boom. China's shifting demographics, discussed below, will require the government to start paying down its debts in the coming years as well, putting a limit on the government's ability to borrow going forward. Beyond the fiscal constraint limiting China's ability to re-up its borrowing, the financial sector is creaking under the debt from the 2009 borrowing binge.

Figure 5: Support for Investment Growth Is Waning

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, People's Bank of China, Ministry of Finance

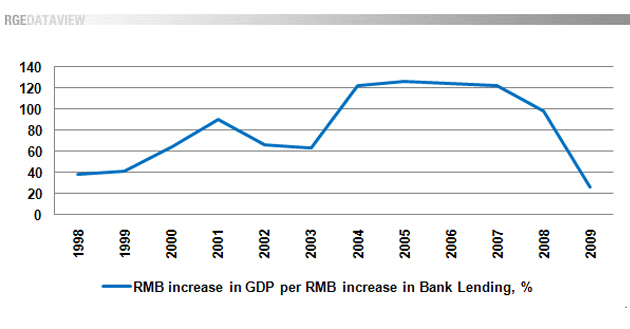

China's banks are undertaking a massive recapitalization this summer, but they will be unable to increase their lending to the 2009 level. The four largest listed Chinese banks will raise more than RMB250 billion in capital this summer, but this will add less than two percentage points to their capital adequacy ratios, which are hovering just above the regulatory minimum. Most of the extra capital will have to be set aside as a firewall to protect against a coming surge in nonperforming loans (NPLs), detailed below. Regulators could lower the required reserve ratio to free up more funds for lending, but given that the banks continue to park excess reserves at the central bank, this probably would not have much of an effect. As long as Chinese banks are focused on protecting their capital, the government will find it difficult to engineer another surge in lending without putting the financial system at risk. In terms of GDP growth, last year's lending binge was the least efficient since the late 1990s banking reforms, suggesting a relatively large portion of borrowers will be unable to repay their debts. Though balance sheet worries have not stopped Party leaders from directing state-owned banks to lend in the past, reforms in the late 1990s have given Party technocrats within the central government greater influence over the financial system, which should prevent the Communist Party from pushing the financial sector into a crisis. (See "In China, Politics Trump Monetary Policy" for a discussion of the political economy of Chinese lending.)

Figure 6: Lowest Efficiency of Bank Lending Since 1990s Reform

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, People's Bank of China, RGE

Even if another debt-fueled investment binge is out of the question, the strong balance sheets of Chinese firms should help minimize the risk of a sharp slowdown in investment. Retained earnings continue to supply about 60% of the funds for investment in China, which should keep fixed capital formation elevated in the coming years. Additionally, continued urbanization and the need to reduce the economy's energy intensity will provide plenty of opportunities for relatively high returns. Meanwhile, structural changes in the economy suggest consumption soon will outpace investment growth and thus reduce GFCF's share of China's GDP.

The Structural Factors

China has been able to maintain high investment levels for decades due to falling real wages and an elevated savings rate, but the structural underpinnings for this trend are beginning to disappear: The “excess†supply of labor is disappearing, and shifting demographics and government policies will bring down the savings rate. These changes will result in a marginally higher cost of capital in China due to lower expected returns and slower capital accumulation, which will weigh on investment growth going forward. Lower savings rates will lead to stronger consumption growth at the margins, but this will be insufficient to fully offset slower investment growth, and overall GDP growth is likely to be lower in the next decade than the previous two. In part this is a stock and flow issue, as consumption's share of GDP is lower than that of investment.

For decades, the growth of wages has lagged that of productivity, causing labor's share of national income to fall from 57% in 1983 to about 37% in 2005, where it remains. This was driven by demographic factors that will soon start to reverse, and wage growth looks to outpace overall growth in the coming years, contributing to a slightly higher trend inflation rate and lower returns on capital. China's supply of cheap labor seems to be drying up, which has contributed to labor strife at some of the manufacturing centers on the coast. China's fertility rate fell below the replacement rate at the end of the 1980s, after hovering near that level for about a decade. As a result, the working-age population is forecast to peak in 2014 at 991 million, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates published earlier this year. But even this understates the shift in China's labor force, as the supply of young workers from the countryside likely already has peaked, and the population of 15-24 year olds is forecast to shrink 30% over the next decade. Additionally, those workers now migrating from rural areas to the coastal manufacturing hubs are doing so for different reasons than their predecessors a decade ago. Surveys suggest that migrant workers tend to leave their villages not to send money back to their parents, who by and large are now economically better off, but rather for self-improvement. The result is a more demanding workforce, more frequent job hopping and higher reserve wage levels in the bargaining process. Additionally, rising housing costs in the coastal cities and health insurance based on their household registration have encouraged migrant workers to seek employment closer to their home villages. The sharp decline in Chinese exports at the end of 2008 briefly masked the resulting labor shortages, but as the global economy has recovered so have migrant workers' demands. In RGE's view, the increase in some industries' migrant wages in early 2010 is a continuation of this trend from 2008. The removal of the stimulus in 2011 may temporarily ease these pressures as the infrastructure buildup of the western and central provinces slows and some of the resulting jobs disappear, but labor shortages will continue to be a recurring problem for China's manufacturers.

Figure 7: A Peak in the Labor Force (millions)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Although China's labor pool will not be expanding beyond 2014, government policies could sharply increase labor productivity and alleviate some of the inflationary pressures from the resulting higher wages. However, this would require reforms beyond what the government appears to be contemplating. The household registration system, hukou, to which social services and land ownership are tied, creates artificial labor rigidities in China by making migration from rural areas to urban centers difficult. The government has announced plans to weaken the hukou requirements for Tier 2 and 3 cities, but it will take additional reforms to rural land ownership rules to free up a greater share of the surplus labor in the western and central provinces, which may still be as high as 200 million people. The five-year economic plan that will be presented to the National People's Congress in March 2011 could include steps in this direction, but any relevant measures are likely to be incremental, and reform will be slow. Some of the coastal cities that have experienced labor shortages in recent years have begun introducing programs to allow some migrant workers to gain urban status, but regulatory hoops will make the benefits less attainable.

Wallets Begin to Open

China's unusually high savings rate is likely to start declining over the course of the next decade, which also will contribute to a slightly higher cost of capital as a greater share of income is diverted to consumption at the margins. There are data problems that contribute to a slight overstatement of China's savings rate (imputed rents are implausibly low and retained earnings of foreign firms and consumption of services are undercounted, while continuously rising inventories inflate corporate savings), but even after accounting for these factors China's savings rate was probably about 50% of GDP in 2009, up from about 36% in 2000. This rapid surge in savings outpaced the rise in investment, resulting in China's large current account surplus. All three savings contributors (households, corporations and the government) have relatively high savings rates by international standards, but all are likely to marginally decrease their savings rates over the next decade. This is not to say that China is about to enter a period of dissaving, but rather that the marginal propensity to save will slowly decline in the coming years.

Household savings rates are demographically driven by China's rapidly aging society, as well as structurally motivated by the weak social safety net and financial repression that reduce net interest income. According to U.S. Customs Bureau estimates, 66% of the population was of working age in 1990. Over the next two decades this increased sharply, and the bureau now expects the share of the population aged 15-64 to peak at 73.6% in 2011. As a result, a growing portion of the population has been in a peak savings phase of life each year since 1990. Life-cycle savings patterns suggest that the household savings rate will begin to decline as the working age share of the population begins to contract. The 1997 pension reforms also contributed to the spike in household savings rates, but the shock of the transition from a pay-as-you-go system to a mostly defined-benefit system should have filtered through by now. Contributing to a lower household savings rate will be gradual improvement in China's health-care system. The government plans to spend about RMB850 billion over the three years through 2011 to establish basic universal health insurance coverage. Though out-of-pocket expenses will remain substantial and coverage is tied to household registration, this should marginally reduce the need for precautionary savings. Another contributor to the high savings rate has been financial repression, which has eased only somewhat in the past decade. Artificial caps on deposit rates have reduced the net interest income that households would have earned on their savings, requiring a higher savings rate due to a lack of alternatives. Household savings rates are likely to remain elevated considering the holes in the social safety net and continued financial repression, but demographic trends will reduce households' marginal propensity to save going forward.

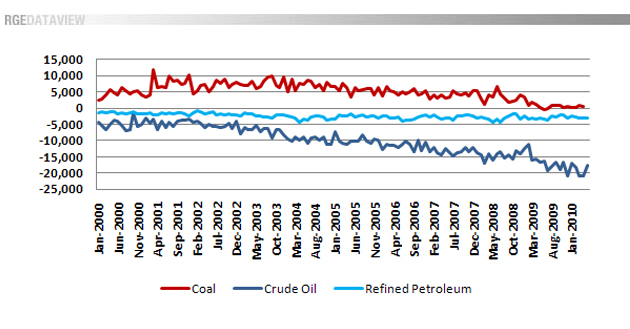

Artificially low labor and energy costs have boosted China's corporate savings rate, but wages are set to rise, as argued above, and energy prices also are likely to increase for Chinese firms. China is on the verge of becoming a net-importer of coal, of which it has abundant resources, due to industrial inefficiencies and controlled electrical prices. Whether through industrial consolidation, higher import levels or more market-based pricing, China's coal prices and electricity prices will have to converge toward global levels. This will reduce returns marginally for some of the energy-intensive industries (steel, iron, aluminum) that have helped drive China's high savings ratio and investment growth in the past.

Figure 8: China's Energy-Related Net Exports (thousands of tons)

Source: General Administration of Customs, RGE

Higher government savings rates have been driven partially by the need to prefund some pension contributions due to the rapidly aging population. The National Social Security Fund (NSSF) was set up in 2000 to help meet the coming shortfall in the government's implicit pension liabilities. At the end of 2009, the NSSF reported assets worth RMB776.5 billion. It is not clear when the fund will begin making payments, but with less than 3% of GDP in assets, the NSSF will continue to have only a marginal impact on China's savings rate.

The most important factor behind the rising government savings rate has been the shift in political economy in China from the 1980s, when local leaders began to be rewarded for GDP growth achieved by any means necessary. To reach the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), cadres are required to serve at least one rotation heading up a poor province or territory, and previously the easiest way to boost local growth rates during the rotation was ramping up investment. This led to an arms race of sorts in heavy industry and infrastructure investment and contributed to the continued weakness of the financial sector and persistent industrial overcapacities. The appointment of Li Yuanchao, a close ally of President Hu Jintao, in 2007 to head the CCP Organization Department should have helped break this cycle, but the scramble to limit the impact of the global financial crisis led the CCP to temporarily emphasize economic growth above all else. As long as a global double dip can be avoided, there should be marginal improvement in the cadre promotion system that will result in a slightly lower propensity among local governments to save and invest. Recent reforms will boost the monitoring of the economic data produced locally and push leaders to perform on a more holistic set of indicators than GDP growth alone. Additionally, the introduction of a property tax, as proposed by several Chinese think tanks and some local leaders, would go a long way toward regularizing local government revenues, which would also reduce the need for governments to build up savings.

During the transition to less-investment-reliant growth, it is possible that China's investment flow could slow more sharply than that of savings, since the former will be slowing for cyclical reasons while only structural forces appear to be behind the coming slowdown in savings. This would result in a slightly larger current account surplus in the next few years, which could spark problems for the global economy. The recently announced RMB reforms could help narrow the current account surplus; however, the increased flexibility in the exchange rate is likely to underwhelm appreciation expectations. Regardless of China's current account position, as investment peaks due to cyclical factors and then declines due to structural shifts, China's GDP growth will slow and the risk of a financial crisis will increase. However, in RGE's view, a major financial crisis still seems unlikely.

IV. The Reckoning: China Will Avoid a Financial Crisis

One of the main reasons that China is likely to avoid a full-blown financial crisis when its investment flow begins to taper off is also one of the structural factors that contributed to the country's high savings and investment rates. Financial repression, while suboptimal in just about every other respect, will shield China's banks during the transition.

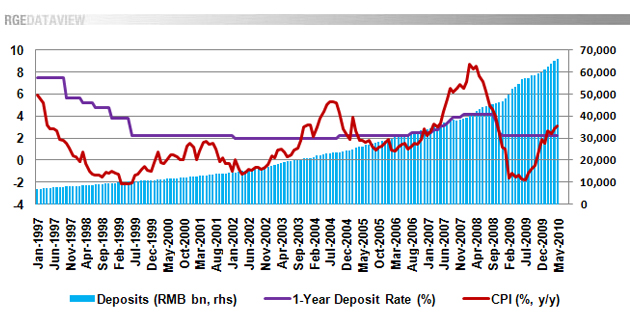

To pursue an investment- and heavy industry-led development strategy, China has repressed its financial system to protect the near monopoly of its state-owned banks. China has maintained high barriers to entry to the banking sector, required banks to set aside a relatively large share of their deposits at the central bank, restricted the development of debt and equity markets and, most importantly, controlled interest rates. China's government sets a cap on the interest rates that banks must pay for deposits and a floor on the interest rates at which they can lend these funds. The resulting spread provides the state-dominated banking sector with a comfortable net interest margin, which in the past has prevented solvency concerns from evolving into a liquidity crisis. As late as 2004, the banking sector was technically insolvent, but financial repression forced deposits into the banks, and the liquidity from the resulting net interest income kept banks afloat.

Although there has been some easing of financial repression in recent years, mostly in the deepening of the corporate bond market and expansion of the equity market, China's financial system remains repressed and interest rates are still government controlled. This will provide some stability as NPLs mount from the lending binge of 2009 by providing the liquidity that the banks will need to write down and roll over some of the bad loans. The government's continued dominance over the banking sector should prevent a run on any of the banks, as deposits are widely considered a contingent liability of the government. Additionally, the lack of any alternative investment vehicles means that banks will continue to attract deposits even as they earn negative real returns.

Figure 9: Despite Negative Real Rates, Deposits Continue to Flow to Banks

Source: People's Bank of China, National Bureau of Statistics

Financial repression also will help to make the transition to slower investment growth a gradual one, as the government can prevent banks from cutting off financing to existing projects. Although the cost of capital will increase marginally in the years ahead, financial repression will mute the price signals that would normally result in a sharper slowdown in investment, at least for those firms that have access to credit from the state-owned banking sector. This should prevent rational risk management decisions on an individual bank level from aggregating into a broader financial crisis. The discussion surrounding the economic plan for the 2011-15 period suggests that the CCP is aware that investment growth must slow going forward, but Party officials also have been adamant that existing projects will continue to receive financing to prevent any sudden stoppages. The Five-Year Plan is expected to encourage increased investment in public housing, hospitals and schools, while restricting further investment in heavy industry. This plan should be supportive of consumption growth going forward, though it also will ensure the slowdown in investment growth is gradual.

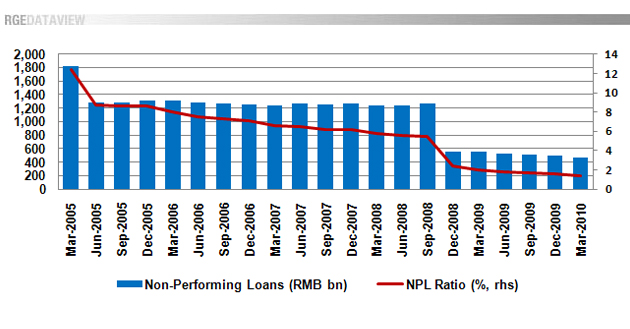

Regardless of the government's plans and ability to direct lending, NPLs are set to increase in China. RGE estimates that China's NPLs will increase by about RMB1.7 trillion as a result of the lending surge that began in November 2008. As credit is gradually tightened in the next three years, this will boost the total amount of NPLs to about RMB2.2 trillion (US$320 billion), of which the banks currently have provisions to cover about one third. In RGE's view, the financial system will be able to withstand the coming onslaught of bad loans, largely because deposits are unlikely to flee from banks with bad loans and the government will step in to inject additional capital if necessary. Still, as the cost of capital increases and expected returns on investment decline, financial reform will be necessary to prevent a more serious financial crisis further down the road.

Figure 10: China's NPLs Set to Surge Again?

Source: China Banking Regulatory Commission

The next phase of growth in China will require a more efficient allocation of capital than China's repressed financial system can provide. The previously planned path toward efficiency, which would have allowed foreign banks to compete directly with state-owned banks starting in 2007, looks uncertain. China's WTO commitments required it to open the banking sector to foreign competition by 2007, but the global financial crisis put that plan on ice as foreign banks were forced to sell off their shares of Chinese banks to raise capital. Domestic politics are likely to limit foreign competition entering the Chinese market in the next few years, and global banks are likely to stay retrenched. Although Party technocrats within the central government will gain some additional control over the banking system in the next few years, they are unlikely to push for the broader reforms necessary to prevent the buildup of bad loans in the future.

Delayed financial sector reform is a worrying prospect for Chinese inflation because it implies that although the cost of capital will increase, credit still will be artificially cheap. China's inflation over the past decade was remarkably muted, thanks in part to wage growth that lagged productivity and thereby contributed to keeping demand-side pressures contained. If wages are to become inflationary going forward, China's monetary policy will need to be tightened to prevent loose credit from contributing additional inflationary pressures. If this tightening comes from the administrative tools that China's regulators have historically preferred, it will induce less-than-optimal growth due to a misallocation of capital. Since financial repression and the resulting need for capital injections are effectively taxes on households, China's growth will be restrained during the transition toward improved domestic consumption unless credit allocation becomes more market-based. If private consumption is to drive growth going forward, interest rates will have to be liberalized and risk management at banks will have to be improved to prevent the need for additional capital injections.

V. Conclusion: Slower Growth Ahead

Although China looks likely to avoid a crisis amid the transition to slower investment growth relative to consumption, its overall growth rate will surely come down over the next decade along with its potential. In the five years through 2010 China will have averaged an annual growth rate of 10.6%, assuming RGE's forecast for 10.1% growth this year is correct. If China follows the path of the other Asian countries that saw their investment peak as a share of GDP but were able to avoid a financial crisis, China's growth could slow to an average of 7.8% in the next five years.

Assuming the Five-Year Plan currently being drafted manages to slow investment growth only slightly, RGE expects China's economy to expand 8.2% in 2011 and around that pace for the next few years. The CCP's economic planners could achieve a higher growth rate next year by forcing the banks to lend at a reckless rate once again, but this only would increase the costs down the road. While it does appear that China's planners understand this risk, a slowdown in global growth in H2 2010 may prolong China's overly accommodative monetary and fiscal policies. Our forecast for 8.2% growth in 2011 assumes only a modest tightening of monetary conditions this year and a fiscal mini-stimulus early next year to ease the cyclical slowdown in investment. If China opts for a mini stimulus, investment may peak in 2011; without one it will peak this year. Although still-loose monetary conditions and another stimulus will prove inflationary and supportive of asset bubbles, the risk to overall growth does not appear too serious. China's trend consumer price inflation has been a bit over 2% for the past decade. Rising wages (and an adjustment to the data to account for a larger portion of income being spent on housing) should push trend inflation up slightly over the next decade, perhaps to around 4%. Even assuming financial repression remains in place, interest rates will have to tick up slightly to compensate for the higher trend inflation rate. If the government opts for more stimulus during the transition or keeps interest rates suppressed for longer than expected, the risk of stagflation in the next five years would increase substantially. The announcement that the RMB once again will be allowed to trade within the 0.5% daily band is positive in this respect, as it will allow for greater flexibility in China's monetary policy. The risk, however, is that the PBoC will allow RMB appreciation to substitute for broader tightening measures and keep interest rates on hold longer than needed. This would only increase the need for more strident tightening measures down the road and push China closer to boom and bust.

Chinese investment is likely to peak near 50% of GDP in 2010 or 2011. In the coming years, cyclical factors, like the removal of the fiscal and monetary stimulus measures from late 2008, will slow the rate of investment growth. Structural forces, like the coming peak of the country's labor force, will permanently increase the cost of capital in China and limit the government's ability to ramp up investment to the pace of 2009. While this transition will herald the beginning of a long awaited turn in China's economic structure toward domestic consumption, it also will usher in an era of lower growth rates. A study of other Asian economies that have made this transition suggests that the risk of a financial crisis will be elevated in the next few years, though the process need not be catastrophic. Judging from the June 19 return to a managed float for the renminbi and the discussion surrounding the drafting of the next Five-Year Plan for the economy, it appears that policy makers are aware of these risks. Although financial repression will help to ensure that China's banking sector survives the transition toward consumption-led growth, in the medium term the financial sector will need to be reformed or China's growth will slow even further. Regardless, lower growth rates going forward will be unavoidable for China. Its current account surplus may increase slightly as the slowdown in investment growth outpaces the decline in China's savings rate, which would challenge global rebalancing.

Chinese investment is likely to peak near 50% of GDP in 2010 or 2011. In the coming years, cyclical factors, like the removal of the fiscal and monetary stimulus measures from late 2008, will slow the rate of investment growth. Structural forces, like the coming peak of the country's labor force, will permanently increase the cost of capital in China and limit the government's ability to ramp up investment to the pace of 2009. While this transition will herald the beginning of a long awaited turn in China's economic structure toward domestic consumption, it also will usher in an era of lower growth rates. A study of other Asian economies that have made this transition suggests that the risk of a financial crisis will be elevated in the next few years, though the process need not be catastrophic. Judging from the June 19 return to a managed float for the renminbi and the discussion surrounding the drafting of the next Five-Year Plan for the economy, it appears that policy makers are aware of these risks. Although financial repression will help to ensure that China's banking sector survives the transition toward consumption-led growth, in the medium term the financial sector will need to be reformed or China's growth will slow even further. Regardless, lower growth rates going forward will be unavoidable for China. Its current account surplus may increase slightly as the slowdown in investment growth outpaces the decline in China's savings rate, which would challenge global rebalancing.