.

. Fossils are the remains of animals or plants that are preserved in the rocksIt is very unusual for complete organisms to be preserved and fossils usually represent the hard parts such as

bones, shells or tests of animals and the leaves, seeds or woody parts of

plants. Fossils may be internal moulds (for example most of the ammonites),

external moulds (for example brachiopods) or the original material impregnated

with chemicals from the surrounding rocks (for example vertebrates).

Alternatively they maybe indirect evidence of life in the past such as

footprints, burrows or borings. Most trace fossils, however, are readily identifiable

by reference to similar phenomena in modern environments. This is how evidence of life is thought to be found in ancient rocks that are dated as old as 3.5 billion years.  .

.

Fossils are found in most sedimentary rocks and are particularly common in lime stones and some shales. The majority of fossils represent aquatic animals, as conditions for preservation are usually better in aquatic environments than on land. In many cases terrestrial animals and plants are preserved only in aquatic sediments, either in the sea, rivers, lakes or estuaries. For example, fossil land mammals are often found in the same deposits as fish, crocodile and turtle remains, which indicates aquatic conditions at the time of deposition,

Remains of soft‑bodied organisms are known, and even jellyfish may be fossilized in very special conditions, The vast majority of fossils, however, consist only of the hard parts of the organism, and in general the possession of such hard parts may be regarded as an essential prerequisite for fossilization. Even the hardest parts of an organism will be broken down or dispersed if they are exposed to scavenging animals, bacterial action or the weather, and for fossilization to occur it is essential that these factors be excluded; rapid burial shortly after the death of the organism usually ensures this. The medium in which the remains are buried may vary widely but the commonest materials are muds, sands and volcanic ash. Some of the more spectacular fossils result from preservation in special conditions, for example insects preserved in amber which is itself fossil resin, the complete mammoths preserved in the permanently frozen ground of Siberia, or the hundreds of thousands of mammal bones preserved in the far pits of California.

Many remains of Caenozoic invertebrates and vertebrates represent the original material of the animal. It is often unchanged chemically or may simply be impregnated with minerals, such as silica or calcite, that enter in solution from the surrounding sediments. This process tends to increase the weight and the hardness of the fossil and is known as petrifaction. Alternatively chemical changes may occur in the material of the remains leading to recrystallisation. This rarely affects the appearance of the fossil but may totally alter the fine structure. In many cases, especially in Palaeozoic and Mesozoic fossils, the original material of the organism may have been entirely dissolved away. This tends to leave a space in the consolidated sediments that may become occupied by minerals from the surrounding rocks‑a process known as replacement. If this occurs gradually as the original molecules of the remains are dissolved away. Then the fine structure of the organism will be preserved. If the solution of the original material is rapid, however, and replacement is not immediate, then the original structure will be lost although the original external appearance may be retained, Some replaced fossils are very beautiful especially if the replacing material is silica or some of the iron compounds such as pyrite (iron sulphide). In some cases the tissues of the organism maybe converted into a film of carbon‑a process known as carbonization. The results of this process are well demonstrated by some of the plants and the graptolites.

The oldest fossils known are found in rocks of the Cambrian period which started 600 million years ago.

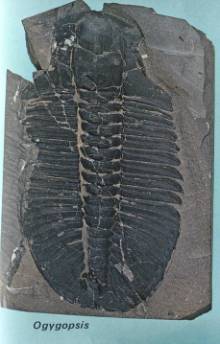

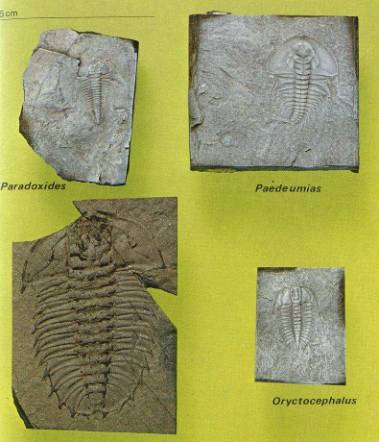

Examples of fossils found in rocks of that period are shown below:

Ogygopsis Cambrian medium‑size to large. Elongate: tail larger than head. Glabella parallel‑sided with faint cross‑grooves: eyes long and narrow: front border wide and flattened, genal spines short (not shown here) Thorax about eight segments, axis strong and Wide, pleurae with deep wide pleural furrows Tail about ten segments: axis tapering, tail pleurae with deep segmental grooves and furrows, back edge with convex border and smooth outline.

and some others

Paradoxides Cambrian: INA E At Australia Head much larger than tail, Glabella expanding forwards, carrying about three pairs of cross‑furrows. eyes large: genal spines about half body length, thorax of about eighteen segments: pleural furrows strong and diagonal, pleurae produced as spines at sides, which increase in size backwards. Tail small with straight back edge

Paedeumias Cambrian: INA E Asia Head large with flattered cheeks. Glabella deeply furrowed. Rounded swelling at front of glabella is connected to front border by a ridge; genal spines long Thorax about fourteen segments, decreasing in size backwards from the second first segment with short spine; second large with spine extending back beyond tail region, other pleurae with long spines; pleural furrows deep. Tail small, carrying long spine (twisted to left in the specimen shown here),

Olenoides Cambrian: NASA Asia Head and tail about same size Glabella with several furrows. expanding slightly forwards and reaching front border: eyes medium‑sized: front border convex and wide, genal spines short Thorax about seven segments; axis wide and tapering with cross furrows and tubercles or spines on each segment: pleura. produced as short spines, Tail of at least five segments with axis tapering backwards: back edge with several pairs of spines.

Oryctocephalus Cambrian: INA SA E Asia Tail and head almost equal in size. Glabella parallel‑sided with three or four pairs of cross‑furrows which have deep pits at each end, eyes small: genal spines long (not clearly shown here). Thorax about seven segments; pleurae produced as spines: pleural furrows deep and diagonal. Tail axis with six cross‑grooves sides and back of tail produced as long spines (not clearly shown here)

See organic fossils (amber and ambergris).

Other sites on fossils