Traduction en français.

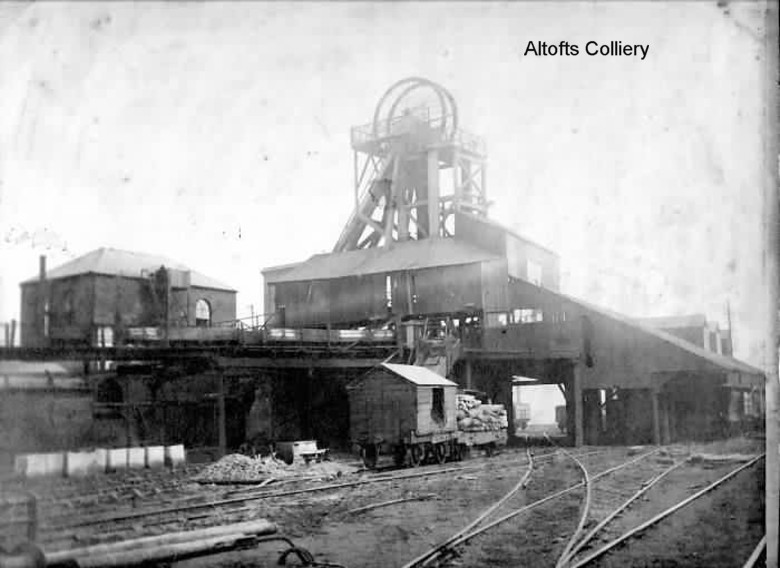

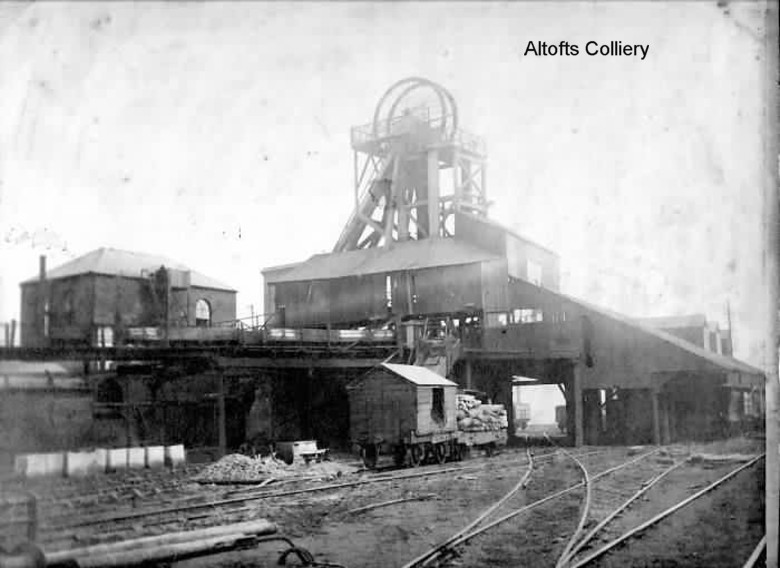

History of coal in the West Riding of Yorkshire; Altofts

and its relation with my family Ratcliffes and Martins.

This story is extracted and reformated from the writing of notes for John Buckingham Pope by Owen Pope a descendant of the Pope family owners of collieries at Altofts. The original source is here [link]. The story relates to my own family on my father's side: Allen William Ratcliffe and Abraham Martin who both worked at Altofts colliery. Abraham Martin came from Birmingham area; he was underviewer at the colliery and in his later years undermanager. He died in March 1914. William Ratcliffe, Allen William Ratcliffe's father was a coal miner at Altofts; he had come from Ilkeston Derbyshire where he was a stone miner (see birth certificate of Allen William). Allen William was educated and trained at Pope and Pearsons dedicated school at Altofts and became an engine tender. He married Ann Martin daughter of Abraham Martin in 1884 and in 1889 he was sent to Calais by Pope and Pearsons I suppose as site manager for the unloading of their steamships exporting coal from Altofts from the port of Hull. This lasted during the golden age until 1914. After the first world war, Allen William Ratcliffe founded with other English residents in Calais, a wholesale cooperative society using the expertise of the Altofts and Normanton Co-operative Society, Ltd, the co-op or CWS of Altofts, and I suppose with the help of its managers and of Pope and Pearsons. I am grateful to Owen Pope for this knowledge coming at the end of my life. Italics are my inputs.

This story is extracted and reformated from the writing of notes for John Buckingham Pope by Owen Pope a descendant of the Pope family owners of collieries at Altofts. The original source is here [link]. The story relates to my own family on my father's side: Allen William Ratcliffe and Abraham Martin who both worked at Altofts colliery. Abraham Martin came from Birmingham area; he was underviewer at the colliery and in his later years undermanager. He died in March 1914. William Ratcliffe, Allen William Ratcliffe's father was a coal miner at Altofts; he had come from Ilkeston Derbyshire where he was a stone miner (see birth certificate of Allen William). Allen William was educated and trained at Pope and Pearsons dedicated school at Altofts and became an engine tender. He married Ann Martin daughter of Abraham Martin in 1884 and in 1889 he was sent to Calais by Pope and Pearsons I suppose as site manager for the unloading of their steamships exporting coal from Altofts from the port of Hull. This lasted during the golden age until 1914. After the first world war, Allen William Ratcliffe founded with other English residents in Calais, a wholesale cooperative society using the expertise of the Altofts and Normanton Co-operative Society, Ltd, the co-op or CWS of Altofts, and I suppose with the help of its managers and of Pope and Pearsons. I am grateful to Owen Pope for this knowledge coming at the end of my life. Italics are my inputs.

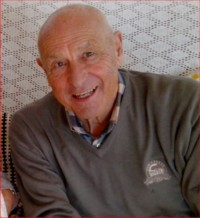

My father's family history is therefore related to coal and Altofts during the industrial revolution in England and the development of coal in the West Riding of Yorkshire after the building of the railway. As a French descendant of Abraham Martin and Allen William Ratcliffe, I chose to become a mining engineer and graduated from the French school of mines of Saint-Etienne in consideration of this history. My professional life was entirely in mining. And by coincidence, without knowing, I was manager at the colliery of Lagrange of Houillères du Bassin du Nord et Pas de Calais Groupe de Valenciennes (see mon histoire liée au charbon).

The West Riding coal trade received a considerable boost from 1850 when the

completion of the Great Northern Railway opened for the first time on

any large scale the great and increasing coal-hungry markets of London

and the South of England to West Riding coals. Already, during the 1840s

the construction of railways within the North and East Ridings of

Yorkshire, with rail links into the coal-producing West Riding, had

given collieries lying within easy access to the new local steam

railways an advantage in competing with the older canal or

navigation-linked pits for the supply of the regional coal markets.

It was against this background of changing and expanding markets occasioned

by the opening of the new railways that the collieries worked by the

Popes at Crigglestone and later by Pope and partners at Altofts arose.

The first members of the Pope family to appear on the West Riding

scene were Richard and John Buckingham Pope, coal factors and

co-partners of Lower Thames Street in the City of London. Richard Pope

had had dealings in property in London from at least as early as 1827.

In November 1841 the partners are referred to as agents in London for

the sale of coal from the Cliffe Colliery at Crigglestone, near

Wakefield, where pits were being sunk in 1838-41. The owners of the

Cliffe Colliery had some difficulty with the availability of liquid

capital and by 1842 they owed 2,300 Pounds to the Popes on a balancing

of the accounts so that the Popes took over the new colliery, sinking

number one shaft deeper and completing number two to the Winter seam.

The colliery had four shafts in 1841 and in 1846.

The Popes continued

their London coal business, maintaining their Lower Thames Street

offices and trading in coal from Abbey Wharf, Westminster. Richard Pope

lived at Camberwell and J. B. Pope, who had been born at Newton Bushall

in Devon and was thirty-five years old in 1842, lived at Mornington

Crescent, Hampstead Road. The Popes continued to develop their Cliffe

Colliery which supplied coals to London by water, and a railway was

built (largely a self- acting incline and in part in tunnel) down to the

Calder and Hebble Navigation under wayleaves granted between 1843 and

1846.

Coke ovens, a fire clay works, a stoneware manufactory, brick and

tile kilns and drying sheds and a chemical works were all run along with

and close to the railway. The firm had a fleet of twenty-seven keels,

the Yorkshire river barges, to carry their products. A series of

highly complex legal and financial manoeuvres were ultimately

unsuccessful in assisting the Popes in a difficult period of trade

depression in the coal industry in the middle and later 1840s and a fiat

in bankruptcy was issued against them at the very end of 1847.

Ultimately, in June 1849, the colliery was put up for sale by auction

and was purchased by J. V. Broughton for 23,050 Pounds. The

financial difficulties of the colliery had brought J. B. Pope to the

West Riding and some four months after the sale of the Cliffe Colliery a

draft partnership deed was prepared under the provisions of which J.

B. Pope, by now of Castleford and described as a coal merchant and

earthenware manufacturer, was to join Joshua Skidmore, commission

agent, and William Shaw, railway building contractor, both of Wakefield,

in the operation of a colliery at Whitwood and of a pottery and clay

works at Castleford, late Isaac Fletcher's.

Pope was to devote his whole attention to the new business and was to receive a salary of 250 Pounds a year. A new partnership deed was entered into in 1850, Pope

being joined by George Pearson and John Woodhouse, railway contractors

residing in Pontefract. (Pearson could only sign the deed with a mark

and Woodhouse had very poor handwriting!) A first lease of coal was

agreed in 1850, the lease being taken from an absentee landowner, the

Rev. Sir T. G. Cullum, Bart., M.A., J.P., D.l., of Suffolk (1777-1855).

Richard Pope, J. B. Pope's eldest son, cut the first sod of one shaft of

the new colliery on his twenty-first birthday in February 1851.

The new pit was named California, after the then-recent California Gold

Rush. One shaft was sunk close to Altofts railway junction, giving

access to all parts of the country. Another (probably for pumping) was

sunk near to the present Wheatsheaf Inn in Whitwood township.

Coal had been mined at Altofts in earlier times - the writer has a deed

of the 1330s which refers to pits of sea coal in Altofts, and there are

references of about 1600 - but no modern coal shafts existed in 1851 in

the township. In any case, Pope and his partners were preparing to work

in the much deeper and hitherto unexploited Stanley Main seam. The

potential of the deeper seams had, it is interesting to note, been first

exploited by Henry Briggs and Charles Morton who had taken a lease

of coal in Whitwood in 1841 from the Earl of Mexborough.

The colliery at

Altofts was early given the name of West Riding from its principal

shafts' situation within the angle formed by the railway junction,

already known as the West Riding junction. One of Pope and Pearson's

letterheads with an engraved illustration and used in 1860 shows a busy

scene at the colliery. Richard Pope senior died in January 1853 and a

few months later Woodhouse left the colliery partnership. The firm now

became Pope and Pearson, the name under which it traded until

Nationalisation - and under which it does still trade (1977).

By

1855 Richard Pope, the son of J. B. Pope and the young man who had cut

the first sod in 1851, had joined the partnerships and it was his energy

which both established and developed the colliery and its trade. The

only early account book which survives begins in 1850, presumably during

the period when coal was being merchanted but not mined; too much coal

was sold in the northern parts of Yorkshire via the York and North

Midland Railway (one end of which is at Altofts Junction) and there were

smaller local sales to potteries (at Leeds and Castleford), to

limeworks, to Carter's Knottingley Brewery and so forth. Other local

markets included a windmill, a flintmill, a bank and a workhouse.

Small and distant sales were made to Chatham and even to Newton Abbot, to

which place there was an established water connection for the transport

of china clay. New coal leases were negotiated in 1851, when a lease

was taken from Hugo C. M. Ingram, Lord of the Manor and a large

landowner in Altofts, and coal was sub-leased from Henry Briggs. Sidings

were put into the York and North Midland Railway in 1853, the year

before it became part of the new North Eastern Railway, and

communication was made with the conveniently close and accessible

Fairies Hill Cut of the Aire and Calder Navigation.

John Buckingham Pope remained managing partner of the concern until his death in April 1878 but his son took a very active part in its affairs and in the coal

industry in a wider context. In 1885 he and his partners were

negotiating for a lease of coal at Rawrnarsh near Rotherham. In 1858 he

and his partners established the modern Sharlston Colliery. He and his

partners sank the great Denaby Main Colliery from 1863 (he, his father

and Pearson were all members of the partnership there), and from 1889

Cadeby Main developed as an adjunct to Denaby.

George Pearson, who lived

in pthe Pontefract suburb of Tanshelf, was the senior partner in a group

of Pontefract men who sank Darfield Main Colliery near Barnsley, in

1856-60. The partners kept the West Riding Colliery's pits up-to-date

technologically. In 1858 they agreed with the patentees to make use of a

coal washing machine, which necessarily resulted in the unusually early

development of colliery pit heaps at Altofts and the neighbouring

part of the Whitwood township. In 1860 William Wood of the nearby

Foxholes Colliery, Methley, recorded in his diary that he went to

Balaciava Colliery, West Ardsley, with Mr Pope, Mr Locke and Mr

Warrington (of Kippax Colliery) to see a coal-cutting machine there.

In August 1869 Pope and Pearson agreed to continue the use of an

experimental coal-cutting machine in their colliery which was worked by

compressed air. The firm was constantly a leader in the field in regard

to mechanical coal-getting. William Garforth, then only recently

appointed manager, introduced two undercutting machines in the Haigh

Moor seam but these, and all other early machines only undercut to

about half the depth which was possible with hand holing.

In about 1888 an electric-powered bar machine was introduced, although Garforth was concerned at the possible effects of the flashes which it made. About

1892 Garforth's own Diamond deep undercutting machine was brought into

regular use at the colliery and from that time the machines became of

increasing significance: mechanical failures decreased and the new

machines were able to contribute towards a shift output per man of six

tons as against a manually-got output of some three and a quarter tons.

Garforth set up his own firm to manufacture coal cutters: he built

twenty-one in 1899 and fifty-six in 1901 and the firm was still

flourishing in 1977. As with many of the new rail-orientated collieries of

the 1840s and, (particularly) the 1850s, the West Riding Colliery was

sunk in what had been hitherto a predominantly agricultural area. Men

had to be recruited to work in the new colliery - often from far afield -

and houses had to be built for them and their families. The population

of Altofts increased to a small extent as a result of the immigration

of railway workers but largely as a result of that of colliery workers

and their families, and especially of those employed by Pope and

Pearson. My own family members Abraham Martin and William Ratcliffe came from Wednesbury and Ilkeston in Staffordshire.

Some colliery families did, however, live just outside

Altofts, where other colliery and industrial developments make any

assessment of the influence of Pope and Pearson's employment impossible

of determination. The 1871 census returns indicate places of birth, and

the colliers who were heads of households in the largely-completed

colliery village of The Buildings at lower Altofts, where the entire

village was the property of the colliery partnership. The 1881 and 1891 census records indicate Abraham Martin and family, the head of family was underviewer in 1881 and undermanager in 1891).

Pope and Pearson's cottage building accounts begin in September 1852, but deeper sinkings and increased outputs demanded more and more workers and more and more

houses for them. In the mid 1860s the three collieries in which the

Popes had interests all began the development of specific colliery

villages, two of which (those at New Sharlston and at Lower Altofts)

still survive in 1977.

The Silkstone seam of coal, lying at some 414

yards below the surface and 4ft. 7in. in thickness, was leased by Pope

and Pearson in July 1863, and the new sinking was paralleled by the

building of the new and model colliery village. The exact date of the

erection of The Buildings at lower Altofts is uncertain (My grandfather's residence as indicated in his marriage certificate was Paley's buildings Lower Altofts), but the site

for the houses was bought by the partners at an auction sale at the

Horse and Jockey Inn in Altofts in April 1864 at the price of 460

Pounds for some 5.5 acres: A letter of July 1864 refers to a proposal

of the firm's concerning their "commencing to build". The sinking to

the Silkstone seam apparently occurred in 1864-65, and the newly-opened

seam gave its name to the new village, Silkstone Buildings.

The dating of the village is further elucidated by a reference in the 1871 census returns to a boy born in Silkstone Row who was then aged six, and by

the stablishment of the colliery community's own Altofts and Normanton

Co-operative Society in about September 1866. By 1871 the streets in

existence were: Silkstone Row, North Street, South Street, East Street

and Prospect Place (my great grandfather Abraham Martin lived in Prospect Place see evidence of this on the marriage certificate of Allen William Ratcliffe with Ann Martin, daughter of A.Martin).

In both 1889 and 1899 Henry Briggs, Son and Co. were

the largest producers of coal among the members of the West Yorkshire

Coal Owners' Association, with Pope and Pearson coming second in both

years.

The question of early labour relations and troubles at Pope and

Pearson's collieries is a difficult subject to deal with, largely on

account of the lack of adequate documentation. Machin's book "The

Yorkshire Miners" details some of the disputes which affected the

collieries from as early as 1853, but gives the men's views only.

Certainly some disputes led to severe conflict and even ejection of

colliers from their houses, although relations never deteriorated to

the extent of those at the sister colliery Denaby Main, which was

constantly and bitterly riven by industrial disputes.

The recollection of old employees of Pope and Pearson is definitely at the present of a sympathetic relationship between masters and men within the last fifty

years of the private ownership of the concern. As was so frequently

the case in regard to major colliery owners in the West Riding, the

Popes were nonconformists, a situation which to some degree cemented

the interests of capital and labour as many of the colliery workmen

were nonconformists by conviction and even before their coming to work

at the new collieries in Yorkshire. My grandfather Allen William Ratcliffe was a non conformist of the Methodist Wesleyan obedience as evidenced by his certificate of marriage with Ann Martin, celebrated in Altofts Methodist chapel).

J.B.Pope was a member of the

Plymouth Brethren and, not surprisingly, two of the meeting houses of

that denomination arose in Altofts: one was dated 1891 and the other

was built in 1906. There is no reference to the existence of this

denomination in the 1878 trade directory, but in the February of the

following year the Brethren were using the colliery company's Pope

Street School for a tea, and by May 1882 they had a Sunday School.

Religious provision did not, of course, emanate entirely or even largely

from the Plymouth Brethren. The Wesleyan Methodists had established a

preaching place in Altofts in 1809, and the Primitive Methodists opened a

chapel in Lock Lane, halfway between Lower and Upper Altofts, in 1871.

Curiously, it was the more staid and respectable Wesleyans, as against

the Prims, who built a wooden chapel at Silkstone Buildings in 1877 at

a cost of 25 Pounds, replacing the denomination's use of a room in

Silkstone Row itself. A new Wesleyan Chapel was erected in 1891,

costing a further 701.18.1 Pounds. and is still in active use (1977).

The Church of England, as was again common, was late on the industrial

scene, W. E. Garforth being behind its interests at the Buildings: the

Mission of the Good Shepherd at Lower Altofts, housed in a corrugated

iron structure to seat two hundred, was opened in February 1903, and

for some years it had its own minister, operating under the umbrella of

the Vicar of Altofts. An early Scout Troop was formed at Lower Altofts

in 1908. Educational facilities were provided by the colliery owners: in

1867 or 1868 a school was built at the end of Silkstone Row by Pope

and Pearson" and the building was used as an infants' school from February

1872 when log books were first kept as a result of the first obtaining

of a Government grant in aid. In the 1891 census my great grandfather Abraham Martin is listed as Colliery Under Manager and Local Preacher [link].

The log books refer to visits made by

the school managers and by the owners - Mrs Pope visited, for example,

on several occasions in 1873 - as well as referring to the frequent

outbreak of infectious epidemics. On the outbreak of an infectious

disease, the company put out posters advising precautions which could be

taken by the tenants against its spread, while the houses infected

were fenced off (Edgar William Ratcliffe grandson of Abraham Martin, son of Allen William Ratcliffe and Ann Martin died of diphtheria in Altofts in 1900 at the age of 13, staying on holidays from Calais with his grandparents.). This school was enlarged in 1895 and its gallery was only removed in 1924. It was not until as late as July 1942 that the management of the school was transferred to trie West Riding County Council, although the building had been leased to the County at a

peppercorn rent in 1903.

A school house was also part of the model village. The school celebrated its centenary in 1972 - apparently quite wrongly. A school was in fact run by the colliery partners from about 1856, and this became the Altofts Colliery School in Pope Street, the log book of which dates from November 1872. A new school was built here in 1875 and old J. B. Pope visited the new buildings on the occasion of

the re-opening in September 1875. The school log book is found here [link] In the 1877-1879 listing line 411 it shows entered 3rd Dec 1877 RATCLIFFE James born 6th Jan 1870 father William Ratcliffe at 26 Silkstone Row Infants School. James was the young brother of Allen William Ratcliffe my grandfather b. 1861. See two entries to the school here.

The H.M.I. did not think much of the

natural abilities of the children: in December 1875 he wrote that "The

general intelligence of the scholars is low and they are very irregular

attenders". This school's management was also transferred to the County

in 1942, and the school was closed in 1946. There is an interesting

reference in the log book in May 1888, when the headmaster refers to his

scholars' parents setting-off to see their relatives near Bristol and

Gloucester and in Shropshire and Staffordshire - the areas from which

they had originally come As I indicated earlier, Abraham Martin came from Wednesbury, and was born in Darleston; William Ratcliffe father of Allen William came from Ilkeston Staffordshire.

Further social facilities were provided in

the form of a recreation ground; the date of its establishment is

uncertain, but is possibly in the 1880s. The printed rules of the

recreation ground survive, headed "Silkstone Row Recreation Ground" -

its location being at the north end of the Row. The Ground was for the

benefit of the tenants of Pope and Pearson, their families and persons

living with them (it will be recollected that there were many lodgers).

A huge committee of sixty persons was to be elected from the

inhabitants, and the Ground, which lay between Silkstone Buildings

School and the canal, was to be open from 6 a.m. to 9.30 p.m. from 1

May to 31 August, and during the winter from 8 to 6. No games were to

be played on Sundays, and fines on adults and exclusion for children for

various periods were provided for misbehaviour.

A new recreation ground or sports ground was opened in September 1924 in a different location. Many colliers had - and still have - a delight in gardening

and (incidentally) in supplementing their wages by growing vegetables.

In 1896 Pope and Pearson supplied some seventeen acres of land for the

use of their workmen at a reduced rental of 25 shillings an acre and

the Altofts Allotments Association was formed for its management:

In 1915 the Co-op committee was asked to allow the use of a room for the

Allotment Association's meetings. Another typical model colliery

village development, backed by the colliery company, was the

establishment of the Altofts Co-operative Society. The minute books of

the Society which have survived date from June 1877, but by that time

the Society had been established for some ten years. It was originally

The Altofts and Normanton Co-operative Society, Ltd., and was formed at

the height of interest in the development of co-operative retail

outlets by individual societies in the new colliery villages of the

West Riding.

No store was opened in Normanton itself, and a

co-operative store was built there in 1872 by an independent Normanton

Society, but it was not until 1894 that the Altofts Society dropped the

name of Normanton from its title. There was another neighbouring

society in the form of the Hopetown and Whitwood Industrial Society.

The Altofts Society was probably established in February 1867, although

according to the successive numbering of its quarterly meetings it may

date back to 1866. It was intended only for employees of the colliery

partnership, and it provided a not atypical range of social facilities

beyond those of a shop alone: by 1872 an educational fund was in

existence, a library existed by 1877 and a reading room was

maintained. A subscription was paid to the Leeds Infirmary to enable

members to obtain treatment there, and in the 1870s references also

occur to tea meetings, lectures and excursions.

The Buildings at lower Altofts had no public house, but the workmen's co-op did sell beer for consumption off the premises, and in 1877 the committee agreed to get a

board painted to caution customers to refrain from drinking beer or

spirits in the streets or in the shop. In 1900 a separate beerman was to

be appointed for the co-op shop - still known as the Top Shop - and

tobacco was also sold. In 1894 it was recommended that non Pope and

Pearson workmen should be eligible as members of the co-op for the first

time, and in 1917 business was booming to such an extent, despite the

War, that the Society had to ask for the tenancy of the adjoining house,

number one Silkstone Row.

As could be expected with a Society so closely allied to the fortunes of the coal trade, booms and depressions in that industry and in its wages were felt in the co-op: the coal trade slumped in 1874 and only recovered slowly, and the sales figures of the co-op show a similar pattern.

Pope and Pearson grew as a large employer of labour: there were 1662 work-men (1316 below and 356 on the surface by 1903, and the firm ultimately became of necessity and design, a major housing owner. By 1928 a list of the firm's property

shows them owning a total of 429 houses, 316 of which were in Altofts,

99 in Normanton and 14 in Whitwood; 388 were freehold and only 41 (all

in Altofts) leasehold.

In 1874 one of the first board meetings of the new company had agreed to buy 38 cottages at Normanton Common which were the property of Mr Pearson. The greatest concentration of company property was, of course, at Lower Altofts, where in The Buildings there were 164 houses; Silkstone Row itself had 52 houses, still in one row

without cross alleys in 1904. An undated list of properties shows that

the dimensions of the Silkstone Row houses slightly differed: One

row, North Street, was of back-to-back houses, the remainder being

through.

The two Portland rows are probably early examples of concrete

houses, similar to those being built (by 1877) at The Concrete near

Wombwell, but now demolished. The colliery schoolmaster recalled that

the company had built 80 new houses between 1871 and 1875. The company

early had its own gasworks, but the supply came from the Normanton

Gasworks from about 1898, when the new Silkstone shafts were sunk on the

site of the gasworks in the colliery yard. Water was supplied by

Wakefield Corporation from 1880, and local government facilities were

(slowly) provided for Altofts by an elective local Board, originating in

1872 and providing, for example sewering from 1878-79 and a cemetery in

1878 My great grand parents Abraham Martin, his beloved wife Ann, my grand mother their daughter Ann Ratcliffe and her son Edgar William who died of diphtheria in 1900 while on holidays from Calais are at rest in this cemetery Photo.

By 1894 Pope and Pearson were paying some 74% of the rates of

Altofts. The colliery village was somewhat altered in the 1890s, when

the ash pits were much improved, and in 1927 a loan was made by the

Altofts Urban District Council for the conversion of the privies in

Silkstone Row. A further social facility was provided at lower

Altofts in the form of an institute for men and boys opened in a

converted malt kiln in the lower part of the village in 1892; in 1911 a

Grand Bazaar was held in the Church Schools in Altofts to raise 800

Pounds for furnishing a new institute, during the presidency of W. E.

Garforth, and a Working Men's Club was in existence in the village by

January 1916.

A yet further and highly important, social facility in the

form of a railway station, to serve Altofts and Whitwood, was opened in

September 1870 photo.

Meanwhile, what of the management of the colliery?

The members of the Pope family were, as has been indicated, much concerned

in the 1860s with the opening up of collieries at some distance from

Altofts - at Denaby Main and at Sharlston - and George Pearson was a

senior partner in Darfield Main. Capital for the necessary new

developments at Altofts was consequently limited, especially after the

collapse of the coal boom early in 1874, so it was decided to turn the

Altofts collieries into a limited liability company, the Pope and

Pearson families taking a majority of the shares - 301,000 Pounds out

of a total capital of 400,000 Pounds. The first meeting of the new

company was held at the firm's solicitors' offices in East Parade in

Leeds on 18th November, 1874, and J. B. Pope was appointed chairman.

Old Mr Pope retired to the Isle of Wight, returning to undertake his duties

as chairman until his death in 1878. His son Richard Pope took over

after his father's death, with the newly-appointed W. E. Garforth as his

strong right hand, Richard was a Congregationalist, unlike his Plymouth

Brethren father, but like his father he had a country estate in the

Isle of Wight, and he died there in 1903.

George Pearson died in 1881, but members of the Pope and Pearson families continued an active interest in the concern. The management of the colliery was largely in the hands of a professional manager, directed initially by the partners

and (from 1874) by the directors and with the aid, for a short time, of a

consulting mining engineer: the great Jacob Higson of Manchester was

appointed to this consulting office, on a part-time basis, in 1874. John

Warburton was the colliery manager until about the end of 1872, when he

was replaced by John Hopkinson, who lived at Normanton and who saw the

colliery through its first years as a limited liability concern; he died

suddenly in London on 14th April, 1879, and was replaced by William

Edward Garforth in that same year: Garforth was introduced at a meeting

of the Board held on 3rd July, 1879 and was paid initially the handsome

salary of 500 Pounds a year.

No detailed account of the life, activities

and significance of William (later Sir William) Garforth is given here,

on account of the recent publication of John MacKinnon's excellent

biography of that gentleman; the work can be consulted at any local

library. By 1875, when the great European coal export trade from Britain

was well developed, a major coal sales depot had been established by

Pope and Pearson at Calais, and by 1876 the company owned steamships

which took the coal from Hull (*).

This was the development of the Cobden-Chevallier free trade agreement between England and France in 1860. My grand-father Allen William Ratcliffe came to Calais from Altofts appointed by his company; I presume as the manager of the coal sales depot - unloading the steamships and the making of briquettes from the slack coal. He often travelled to Hull on those steamships, and sent his children to Altofts for holidays with their grand parents Abraham and Ann Martin and for learning English.

The use of coal washing machinery resulted in the development of pit heaps and also in the availability of large quantities of coal slack; briquettes from this slack were made at both Altofts and Calais, and in 1880 the Board ordered the building of twenty coke ovens at Altofts This implies that the coal from Altofts was coking coal, a feature which explains exports to France by Calais, because coking coal was lacking in the North of France when steel making, based on coke, developed in Valenciennes area; the railway line Calais-Bâle via Valenciennes favoured those exports. In 1881 the Board was considering the

purchase of the unsuccessful Park Hill Colliery near Wakefield, but

decided against the project; a few years later, in 1886, the firm sank

the Fox Pit as an air shaft but close to the canal, a situation which

was considered suitable for the new pit's use as a coal loading place

for the waterway.

In the same year of 1886 there occurred an explosion

in the Silkstone pit of Pope and Pearson at Altofts, where normally some

four hundred men and boys were at work: owing to the explosion

occurring between shifts, only twenty-one persons were killed. Naked

candles had been used in the pit until only six months earlier. The

explosion led to the ultimate invention of Garforth's (the WEG) rescue

apparatus and to the establishment of a series of experimental galleries

near the colliery which cost some 13,000 Pounds in experimental

expenses and, according to the files of the Colliery Guardian, "focused

the attention of the whole mining wold on Altofts".

The first mines rescue station in the world is claimed to have been established in

connection with Pope and Pearson's Altofts Colliery in 1901, and an

Ambulance class was formed in 1884. Pope and Pearson had, of course,

their own colliery locomotives, and railway wagons, and by 1893-94 they

were using between 114 and 117 horses in and about their pits. Thus

there developed at Altofts both a major West Riding colliery and a wide

range of social ancillaries; the colliery was to continue to produce

coal well into the period of Nationalisation, the last coal being drawn

(after the cessation of coal drawing from the colliery shafts) from the

Fox Pit drift on Friday, 7th October, 1966, at about 1 p.m.

See my web site http://pratclif.com and in particular my blog The story of Anglo-French friendship, my blog on coal and mining and my story related with coal and mining.

Photographs:

- Abraham and Ann Martin

- Allen William and Ann Ratcliffe

- Allen William Ratcliffe's passport

- Pitwork: photographs of Joseph Stocks

- Slide show

Mis en ligne le 01/08/2014  pratclif.com

pratclif.com

This story is extracted and reformated from the writing of notes for John Buckingham Pope by Owen Pope a descendant of the Pope family owners of collieries at Altofts. The original source is here [link]. The story relates to my own family on my father's side: Allen William Ratcliffe and Abraham Martin who both worked at Altofts colliery. Abraham Martin came from Birmingham area; he was underviewer at the colliery and in his later years undermanager. He died in March 1914. William Ratcliffe, Allen William Ratcliffe's father was a coal miner at Altofts; he had come from Ilkeston Derbyshire where he was a stone miner (see birth certificate of Allen William). Allen William was educated and trained at Pope and Pearsons dedicated school at Altofts and became an engine tender. He married Ann Martin daughter of Abraham Martin in 1884 and in 1889 he was sent to Calais by Pope and Pearsons I suppose as site manager for the unloading of their steamships exporting coal from Altofts from the port of Hull. This lasted during the golden age until 1914. After the first world war, Allen William Ratcliffe founded with other English residents in Calais, a wholesale cooperative society using the expertise of the Altofts and Normanton Co-operative Society, Ltd, the co-op or CWS of Altofts, and I suppose with the help of its managers and of Pope and Pearsons. I am grateful to Owen Pope for this knowledge coming at the end of my life. Italics are my inputs.

This story is extracted and reformated from the writing of notes for John Buckingham Pope by Owen Pope a descendant of the Pope family owners of collieries at Altofts. The original source is here [link]. The story relates to my own family on my father's side: Allen William Ratcliffe and Abraham Martin who both worked at Altofts colliery. Abraham Martin came from Birmingham area; he was underviewer at the colliery and in his later years undermanager. He died in March 1914. William Ratcliffe, Allen William Ratcliffe's father was a coal miner at Altofts; he had come from Ilkeston Derbyshire where he was a stone miner (see birth certificate of Allen William). Allen William was educated and trained at Pope and Pearsons dedicated school at Altofts and became an engine tender. He married Ann Martin daughter of Abraham Martin in 1884 and in 1889 he was sent to Calais by Pope and Pearsons I suppose as site manager for the unloading of their steamships exporting coal from Altofts from the port of Hull. This lasted during the golden age until 1914. After the first world war, Allen William Ratcliffe founded with other English residents in Calais, a wholesale cooperative society using the expertise of the Altofts and Normanton Co-operative Society, Ltd, the co-op or CWS of Altofts, and I suppose with the help of its managers and of Pope and Pearsons. I am grateful to Owen Pope for this knowledge coming at the end of my life. Italics are my inputs.