ON THE ORIGINS OF LANGUAGES

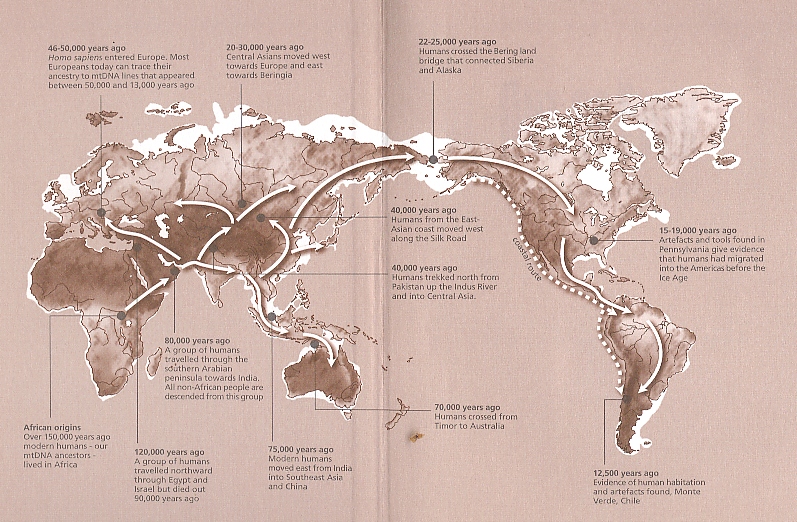

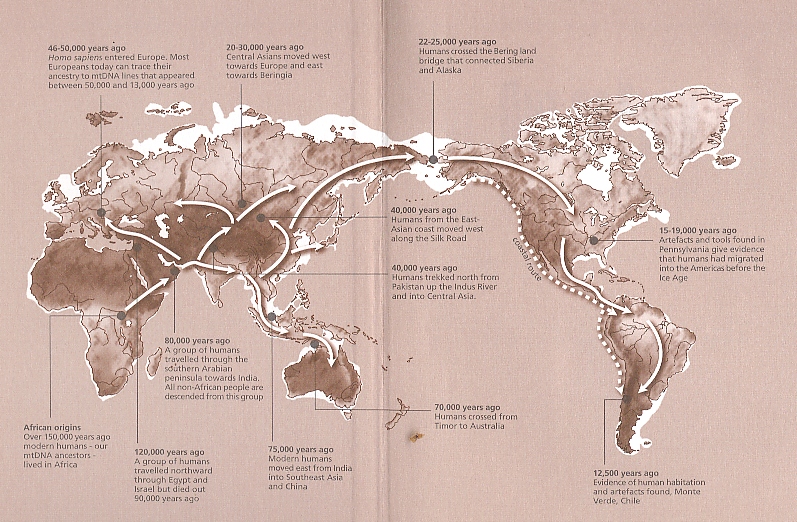

Recent scientific findings about the origins of humanity, based on genetic evidence i.e. the distribution of mtDNA and Y chromosome among the world population of today, suggest that the peopling of the world outside Africa developed from a small group of modern humans (perhaps a few hundred or a thousand) that left Africa about 80 thousand years ago.

These findings give rise to new thoughts about the origins and evolution of languages that necessarily accompanied these migrations of Homo.sapiens and his dispersal throughout the planet. |

Map of supposed migrations according to the distribution of mtDNA  |

Map of supposed migrations according to the distribution of Y chromosome

|

The capacity of modern man (Homo.sapiens sapiens) for the use and development of complex language is a character of modern humans and is related to the evolutionary structure of the brain. There is speculation on the origins of language.

It is probable that this capacity pre-existed and evolved from other hominids. There is speculation on the origins of language in this respect.

Modern humans are the result of millions of years of evolution by the play of both "natural selection" and "sexual selection". The characters developed through this long evolutionary process probably increased the chances of survival of our species, by improving our adaptability to an often hostile natural environment, that is for obtaining food and water, for protection against predators, for protection against cold, and this until the age of successful reproduction and producing of numerous offspring. These characters are bipedism, stereoscopic vision and hearing, two hands composed of five fingers of which one is opposable to the four others, capacity for speech, and a highly developed brain (circa 1400cm3) which coordinates all of this and which makes us capable of foresight, memory, communication, imitation and collective action. All such characters give modern humans an advantage for survival, reproduction and development, even in hostile environments and explains our remarkable physical and cultural development. In particular, the capacity for speech and its coordination by the brain from which language derives, give modern humans the capacity to cooperate, to exchange and accumulate knowledge and experience within each generation and from each generation to the following, and so to pursue and achieve individual and collective goals out of the frame of time.

See summary of a book by Michael Tomasello on the origin of language.

and also the site of Encylopedia Wikipedia on language

A brilliant theory of physiological and biological

structure of language is in "Language:

by Robin Allott". Robin Allott's theory is that in every aspect, language (including every

particular language) is a semi-natural development, partly innate, partly the

product of imprinting. The substance and the structural organisation of language

at every level is determined by, and develops within, the physical, biological and neurological characters of H.sapiens. At no level language is a

purely arbitrary structure or is purely conventional in origin. The natural

character of language in general (and of every language in particular) is derived

from, and formed in parallel with, the structure, content and characteristics of

human perception (particularly visual perception) and from the

physiological and neurological structures which co-ordinate bodily action and

which underlie both language and vision. The lexical and syntactic structures

found in language are derived from and directly related to the processes and

formations found in visual perception and in the organisation of bodily action.

Put most succinctly, the hypothesis is that "WE SPEAK AS WE SEE" and "WE SPEAK AS WE

ACT". This hypothesis on the semi-natural character of language and its relation

to perception and action, applies at every level, that is, at the level of the

production and perception of elementary speech-sounds (phonemes), at the level

of the production and perception of words (the formation of elementary

speech-sounds into words), at the level of the combination of words and groups

or strings of words into meaningful sentences (as an effect of morphological and

syntactic structures and processes) and at the level of linking sentences into

discourse. The drive of the hypothesis is towards a holistic account of human

functioning, of human behaviour - the organisation of usable human experience in

terms of a close interrelation of perception, language and action, going beyond

perception to what might be termed 'ception', that is, the total activity of man

in grasping, structuring and controlling the world, whether intellectually or

physically.

Having Robin Allott's theory in view, a theory which indeed explains many of

the aspects of language, having Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection in

mind, a theory expanded by Richard

Dawkins and backed by modern evidence given by DNA and genetics, and which

marvelously explains the origins of modern man, and having in mind the new

investigations on the migrations of modern man from Africa and the peopling of

the world, I can now revert to the question of the origin of languages.

It is suggested that the 6 billion modern humans living today trace their origins

to an ancestor that evolved from the family of hominids in Africa, about 200 thousand years ago and that all the non Africans trace their origin to an small group (tens or a hundred) of ancestors that left Africa 80 thousand years ago because of dwindling food and water resources, due to the very severe climatic conditions caused by glaciation in the northern hemisphere. Glaciation caused a decrease in precipitations, and the drying up and desertification of Northern Africa. Due to the scarcity of resources, a group of modern humans would have crossed the straits of Bab el Mandab, at the south of the present red sea; the sea level was 80-100m below present; the red sea had become closed from the Indian ocean and sea life forms were therefore diminished, a situation which prompted this group of humans to search for resources accross the straits to the East. Clearly, the speech and language of this small group of humans was limited to the exchange of perceptions, individual and collective action, collective hunting and gathering, and ... reproduction... The complex cultural evolution that took place during the next 80-100 thousand years to this day was simply not there. But this original speech and language had all the basic elements, speech sounds and phonemes that the larynx lips and tongue could pronounce, and the logical structure that the brain could organise for expressing visual perception, corrdinating bodily movements, as well as individual and collective action in the environment of the day. These basic elements explain why they are universal to all modern humans of today.

One important aspect to consider, is the time frame of evolution and development of this original group of humans and their descendants. Starting from an event that took place 80 thousand years ago, this group slowly moved eastwards, following the natural corridors that were offered to them, with glaciation, extreme cold and mountainous areas prevailing to the north which were barriers to moving there. As resources were found and were abundant with favourable environmental conditions, humans developed, and as resources dwindled and environment became more hostile, group numbers were depleted or even became extinct, or sub-groups split from the original group and went further eastward searching for new resources and more favourable environmental conditions. At the time, the formation of large groups of hunters gatherers was not possible due to the distribution of resources and to the limited technologies that were used; life in village communities, with agriculture and livestock raising had not yet been invented (archeological evidence of this dates back to only 10 thousand years in Mesopotamia). One has to imagine that human development and extension evolved over tens of thousands of years. Moreover, as splits and branchings from the original group took place, and each subgroup started a genetic and cultural evolution of its own, separations occurred and such populations were to never meet again, until the progress of technology and culture permitted, but this was many thousands of years afterwards.... The latest of these re-meetings was only 500 years ago when the Europeans discovered America by cross-atlantic navigation, whereas the continent had been peopled from Asia by the straits of Behring 20 thousand years ago (see peopling of the Americas) and (early human habitation of Southern Chile 33000BP). And more about peopling of the Americas.

Over this time span, anthropologists have identified changes in the use of artifacts and most significantly, they designated the Pleistocene and the Paleolithic period as a time of great progress in the technology of hominids. One may realise the timeframe involved by considering that our recent scientific and technological advances in industry, biology, genetics and astronomy date back less than 100 years, that the invention of musical notation dates back 400 years, the invention of modern printing 500 years, the coding of speech and language 6000 years, all this backed by paleontology, anthroplogy and more recently, genetic evidence (DNA).

See site on early Chinese technology transfers to Europe.

Following the model of peopling of the world as depicted by Stephen Oppenheimer in "Out of Eden" (see this model), we may imagine that sub-groups of humans split and evolved separately from each other during extremely long periods of time (compared to latest two millenia). Paleontological evidence shows that tools and artifacts developed in different parts of the world were similar because they served identical functions. We may say that the same applies to the basic elements of speech and language. But there seems to be no reason why identical sounds and phonemes should have been used to designate the same perceptions (visual, or bodily actions, sentiments or abstract concepts...). Similarly there seams to be no reason why the combination of sounds and phonemes into words, and the combination of words (verbs, subjects, objects...) into sentences up to the structure of discourse should have been the same, although a limited number of such combinations can be used. But as we move up in the structure of languages, because the combination of sentences into discourse is related with the human brain and its application to the expression of perceptions and bodily actions, it appears that universality applies to all humans and this is precisely the subject of linguistics. This explains why all languages can be translated either from one to another directly (language A to language B), or indirectly (language A to B, language B to C and from there language A to C).

Stephen Oppenheimer's model of peopling of the world suggests a small number of originating groups, and these are backed by genetic evidence based on the distribution of mtDNA and Y chromosome, and computer simulations of population trees. The original languages of these groups i.e. before they met again with other groups from which they had separated, should superimpose on the genetic data. The following is extracted from Scott DeLancey's Linguistics Homepage (Scott DeLancey is professor at the Department of Linguistics, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, U.S.A).

First, languages are grouped by families.

A language family is a group of genetically related languages. Languages are genetically related if they descend from a common ancestor. For example, French, Spanish, Catalan, Italian, and Rumanian all descend from Latin; therefore they are related.

Modern languages such as German, Flemish, Dutch, English, Icelandic, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish all descend from a common ancestor. But their common ancestor was not written, so we have no written evidence for it, as we have for Latin and Greek. But we know it must have existed, because there is no other way of explaining the similarities of word roots, grammatical endings and syntax, among the modern languages. An ancestral language which has to be inferred by comparing modern languages is called a "proto-language"; we refer to the common ancestor of these languages as Proto-Germanic. This implies that the ancestor of modern germanic languages had not reached a similar stage of cultural development as Latin which is associated with the Roman Empire, the foundation of which dates back 3 thousand years ago only and its apogea only 2000 years ago.

A language, or sometimes a very small group of very closely-related languages, which does not seem to be related to any other language is called an isolate. Basque, spoken in northern Spain and southern France, is a well-known example of an isolate. Quileute and Chemakum, two closely-related languages of Washington State, constitute a small family (called Chemakuan) which can be considered an isolate since it doesn't seem to be related to anything else.

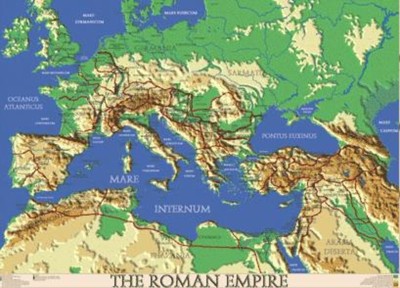

Families of languages as grouped by Scott DeLancey are shown in the following maps:

When the meeting again of human groups was possible, due to climatic change (warming at the end of the last glaciary period), as well as to the development of culture and technology, languages, like genetic pools, started to mix.

Origin and evolution of languages

WE DON'T ASK OURSELVES where languages come from because they just seem to be there: French in France, English in England, Chinese in China, Japanese in Japan, and so forth. Yet if we go back only a few thousand years, none of these languages were spoken in their respective countries and indeed none of these languages existed anywhere in the world. Where did they all come from?

In some cases, the answer is clear and well-known. We know that Spanish is simply a later version of the Latin language that was spoken in Rome two thousand years ago. Latin spread with the Roman conquest of Europe and, following the breakup of the Roman Empire, the regional dialects of Latin gradually evolved into the modern Romance languages: Sardinian, Rumanian, Italian, French, Catalan, Spanish, and Portuguese. A language family, such as the Romance family, is a group of languages that have all evolved from a single earlier language, in this case Latin

But while the Romance family illustrates well the concept of a language family, it is also highly unusual, in that the ancestral language — Latin — was a written language that has left us copious records. The usual situation is that the ancestral language was not a written language and the only evidence we have are in its modern descendants. Yet even without written records, it is not difficult to distinguish language families, as can be seen in Table 1.

Here similarities among certain languages in the word for "hand" allow us to readily identify not only the Romance family (Spanish, Italian, Rumanian), but also the Slavic family (Russian, Polish, Serbo-Croatian) and the Germanic family (English, Danish, German). There are, however, no written records of the languages ancestral to the Germanic or Slavic languages, so these two languages — which must have existed no less than Latin — are called Proto-Germanic and Proto-Slavic, respectively.

If we examine words other than "hand," we find many additional instances where each of these three families is characterized by different word roots (phonetically), just as in the case of "hand, ruka, mano". But we also find, from time to time, roots that seem to be shared by these three families; that is, the same root is found in all three families. What is the meaning of such word roots?

In fact, similarities among language families such as Romance, Germanic, and Slavic, have the same significance as similarities among languages in any one family, for example Romance languages. These similarities imply that the three families are branches of a more ancient family of languages. In other words, a language that existed long before Latin, Proto-Germanic, or Proto-Slavic first differentiated into these three languages and they in turn, diversified into the modern languages of each family. This larger, more ancient family of languages is known as the Indo-European family and it includes almost all European languages (except Basque, Hungarian and Finnish), and many other languages of Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. The Indo-European family of languages has in fact, thirteen branches; in addition to Romance, Germanic, and Slavic, there are also Baltic, Celtic, Iranian, Indic, Tocharian, Anatolian, and three single languages that are by themselves separate branches of the family: Armenian, Greek, and Albanian.

The thirteen branches of Indo-European are connected to one another by numerous common words and grammatical endings. One example is the word for "mouse," which exhibits striking similarities among languages from different branches of the family: Greek "muus", Latin "muus", Old English "muus", Russian "msh", and Sanskrit (Indic) "muu-". Not surprisingly, scholars believe that the original Proto-Indo-European word was *muus- (the * indicates a hypothetical reconstructed form, rather than an actually attested written form). Another root shared by different branches is the word for "nose": Latin "naas-", Old English "nosu", Lithuanian (Baltic) "nos-", Russian "nos", and Sanskrit "naas-". All of these words are thought to have evolved from Proto-Indo-European "*naas-". The precise time and place that Proto-Indo-European was spoken remains a matter of some dispute even today. The two most popular hypotheses postulate it was spoken in Ukraine around six thousand years ago, or Anatolia (modern Turkey) around eight thousand years ago.

The story does not end here, for Indo-European is but one branch of an even larger (and more ancient) family known as Eurasiatic. In addition to Indo-European, this family also includes the Uralic family (Finnish, Hungarian, Samoyed); the Altaic family (Turkic, Mongolian, Tungus, Korean, Japanese); the Chukchi-Kamchatkan family just across the Behring Strait from Alaska; and the Eskimo-Aleut family that extends along the northern perimeter of North America from Alaska to Greenland. One of the words found in all five branches has a general meaning of "tongue", "speak" or "call": Proto-Indo-European "*gal" "call," Proto-Uralic "*keele" "tongue," Proto-Altaic * "tongue, speak," Kamchadal (Chukchi-Kamchatkan) "kel" "shout", Proto-Eskimo *- "inform." The Eurasiatic family is also characterized by distinctive first- and second-person pronouns, the first based on M, the second on T. Within the Indo-European family, almost every language exhibits such forms: English me and thee, Spanish me and te, Russian menya and tebya, and so forth. This pattern is, however, characteristic of the entire Eurasiatic family, not just the Indo-European branch. In other parts of the world, different pronominal systems are found. For example, in the Amerind family, which includes most Native American languages, the most common pattern is first- person N and second-person M.

If we apply this method of classification to languages elsewhere in the world, we can, in similar fashion, distinguish about twelve other large and ancient families comparable to Eurasiatic.

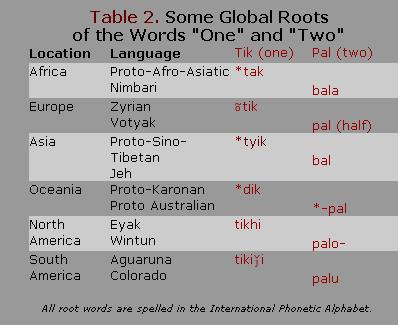

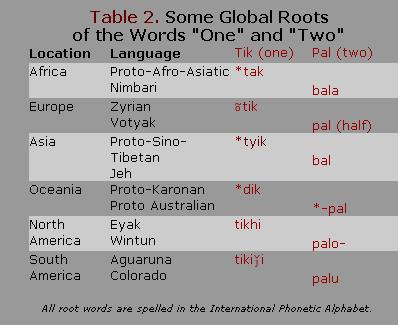

Even among these dozen families, there are certain distinctive roots indicating that all twelve of these families have evolved from a single earlier language. Two of the most widespread roots are TIK 'finger', 'one' and PAL 'two'. Both of these roots are extremely common around the world. Table 2 provides just one example of each from the world's major geographical areas, but many additional examples could be cited.

Table 2:

.

.

There is, however, indirect circumstantial evidence from other areas of science that may provide an answer to these two questions. Both the archaeological record (in terms of bones and artifacts) and human genes (in terms of gene frequencies and mitochondrial DNA) indicate that all modern humans share a recent common ancestry in Africa. What is surprising, and difficult to explain, is that people who look just like us — modern humans — first appear in the archaeological record one hundred thousand years ago. But these people did not behave like us; they are indistinguishable from Neanderthals in both their toolkit and their behavior. It was only around fifty thousand years ago that — quite suddenly — both toolkits and behavior started to change with amazing rapidity. Toolkits that had remained unchanged over hundreds of thousands of years began to change with the rapidity of tennis-shoe styles today. And styles that had been uniform over huge geographical distances began to differentiate in neighboring villages. People began to fashion tools from other materials. Whereas previously only stone had been used, now bone, shells, ivory, and other natural materials were employed. Art appeared for the first time, burials became more complex, and people seem to have spread out of Africa to inhabit the entire world, replacing earlier inhabitants (Neanderthals) or occupying territories hitherto uninhabited, such as Australia, Oceania, and the Americas.

Given that interaction and borrowing are possible reasons for the similiarities between languages, the original African language would have likely been influenced by the languages of the cultures it encountered and theoretically replaced. Merritt Ruhlen explains how that African language developed and why it is considered to be the original fully modern language.

We arrive at the final question in our story. What advantage could have allowed a small African population to leave Africa fairly recently and, in a short time, occupy the entire world and replace all previous human inhabitants? A growing number of scholars — linguists, archaeologists, and geneticists — believe that it was the appearance of fully modern human language around fifty thousand years ago that bestowed this enormous selective advantage on a small African population. If this scenario is correct, then the similarities among the world's extant languages not only support the idea of a recent African origin for all modern humans, they also explain it. The invention of modern human language fifty thousand years ago led to the explosive expansion of modern humans around the globe. And even today traces of this sudden expansion persist in languages around the world.

Persisting in languages around the world are traces of the sudden expansion of humans at the time of the development of the original fully modern language. Merritt Ruhlen discusses how these traces can be seen in certain widespread roots as a result of their common origins

To further understand the origin and evolution of languages, we may first consider the evolution of modern languages and forms of speech ie. the development of argot, slang, cant, jargon, lingo, patois, vernaculars and regional dialects.

Argot, slang, cant, jargon, lingo, patois, vernaculars and regional dialects are "regional" or "social" varieties of a language distinguished by pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary. For example, "cockney" is a variety of English spoken by some Londoners. "Marseillais" is a variety of French spoken in the South East of France. More specifically, a dialect is a variety of speech that differs from the "standard speech" or the "speech of the common individual" within the culture in which it exists. Jargon or cant is a special terminology understood among the members of a profession, discipline, group or class, but obscure to the general population, because they have no use of it.

Argot, slang, cant, jargon, lingo, patois, vernaculars and regional dialects develop because languages change continuously in adaptation to the evolution of social behaviours, ideas, technologies and science. Regional and social dialects, within a community speaking the same language, develop when there is little or no communication possible between the different components or areas where the common language is spoken, due to geography and/or culture eg. science or technology.

In the case of dialects separated geographically or culturally from the main language, given enough time, these will become individual languages. The process applies today to French of France, to French of Canada, to French of Belgium, to French of Switzerland, even when communication between the different communities speaking French are numerous, because each community is separated in its cultural, social, political and institutional structures.

But earlier in the past, this applied all over Western Europe to Latin. Latin was the language of the Romans and of the Roman empire at its apogee from -5000 to -2000 years BC.

See map of the Roman empire with major road links:

After the decline of the Roman empire at the beginning of the first millennium, Latin evolved into the modern languages of French, Spanish, Catalan, Italian, Portuguese, Rumanian, Corsican, Provençal, Sarde, which all derive from Latin. However, the process must have taken hundreds of years. Evidence for this is due to the fact that Latin was a written language highly structured in lexicon, grammar and syntax, of which we have numerous literary records by famous authors for example, Cicero, Seneca, Tacitus, Virgilius, Caesar, and which were studied and copied by scholars up to the 17th century. In fact Latin was the official language of clergy and scholars, of law and contracts, all through the first millennium, the middle ages and until the end of the 17th century. Isaac Newton's notorious treatise on universal gravity was written in Latin. Latin is still taught in European schools today.

How did latin evolve into its many regional dialects and into the modern romance languages spoken and written today? We may imagine that latin, the language of the hegemonic power of the late pre first millennium, spread across the sphere of influence of the Romans and of the Roman empire (see map), within small populations that spoke their own languages inherited from their origins. The replacement of these vernaculars by Latin took place only in areas where romance languages are found today ie. France, Spain, Italy, Rumania, the latter having strongly borrowed words later on, from neighbouring Slavonic languages (Russian and Serbo-Croatian). It seems that Latin completely replaced the vernaculars in these regions of France, Spain and Italy; an explanation for this may be the smallness of the populations and their degree of integration into the Roman empire ie. adoption of its social, cultural, political and institutional structures. For example, French law is considered to be based on the Roman judicial system known by record (Cicero, Seneca..), even after being modernized under Napoleon's rule at the beginning of the 19th century.

Despite their degree of integration within the structures of the Roman empire, the latin that was spoken in the region of Lyon, or in the region of Lutetium (Paris), was not exactly the same language spoken in Rome by Cicero or Seneca or Virgilius. The same applies to French Canadian today. When the Roman Empire declined and eventually dislocated, these dialects continued their own evolution and became languages of their own. But the process took more than a thousand years, because Latin continued to be used as the language of clergy, scholars and contract makers. For example, in French, the first legal contract to be written in "French" was in the 13th century but Latin was still used in the 17th century.

Evidence that Romance languages derive from Latin, come from the study of Latin which offers many written records. The vocabulary, grammar and syntax of these languages have similarities with Latin, in particular words; word roots can be traced to Latin in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and their still regional dialects like Provençal, Catalan, Corsican, Sarde. For example the latin word for hand or derivatives of the same, "manus" is found is all of these languages. Almost all of the word roots that are found in the major Romance languages are found in Latin, exceptions being borrowing from other languages at much later periods nearer to this day and known by linguists, for example from Arabic, or English, or Russian.

In contrast with Romance languages, Latin did not totally replace vernaculars that were spoken in Northern Europe, nor in present day Turkey or the Levant. In Northern Europe, including modern Great Britain, most of the word roots are not found in Latin and are not common with Romance languages. The languages of English, German, Dutch and Flemish, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, all share common word roots so we may formulate the hypothesis that they derive from a common ancestor language, like Romance languages derive from Latin. These languages are grouped in a family which is designated as Germanic, and their common ancestor is designated as proto-Germanic, because there is no written record of such a language, as is the case for Latin.

However, Latin words were probably adopted in these languages at the time of the Roman Empire, and borrowing of words from Romance languages took place at much later periods, notably in England after the Norman conquest in 1066 by William the conqueror. However, it must be said that the Normans were of Northern European origin having occupied North West France (called Normandy today) from the 6th to 8th century. It seems that the Normans had adopted French customs and language at the time of the Conquest, because borrowing of words common with modern French are considered dating back to this period.

In Turkey, Latin did not replace the local vernacular either; modern Turkish language shares words with the so-called Turkic family of languages spoken in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakstan, Kirgistan...

In the Levant, the vernaculars were all semitic languages of which modern hebrew and Arabic. Arabic spread all over the Levant and West Asia in the second half of the first millennium.

Language roots

As explained above, word roots are identified by considering the modern languages that exist in the world today. Working backwards in time from these modern languages, we can understand which of these roots, being common to each language because perceived by their phonetic evidence, may have existed at an earlier time in an earlier language ancestor, even without the need for writing. Writing is the coding of language sounds and it reflects the grammatical and syntactic structure of the language. However, in many instances, writing hides the similarities that may exist between languages because of script (for example Cyrillic script, or Hindu script, or nearer to us Gothic script in German) or use of script signs to code given phonemes (sounds), for example in Portuguese, where the sound "on" as in "bon jour", is coded "boã dia". Decrypting written languages to identify common word roots is the specialized discipline of linguists.

If different modern languages have the same word root (almost phonetically the same), for designating a percept, that is a visual or sensory perception, an abstraction or a concept, then we may formulate the hypothesis that this word existed in an ancestor language to these languages. This applies for Romance languages with Latin, or Germanic languages with the hypothetic (because no records) proto-Germanic language.

The foregoing theories have been developed for modern West European languages, but similar processes are most likely to have taken place in other parts of the world for other languages.

Created on ... septembre 08, 2004

.

.